Projects:

-

Sample Project #1,

Code folder

Lexical scanner - Tokenizer and SemiExpression token collector -

Sample Project #2,

Code folder

Rule-based parser - Parser contains rules which each contain actions invoked if semiExp matches rule -

Sample Project #3,

Code folder

Parser with Abstract Syntax Tree - AST is a container for analysis information, built during analysis, used for display -

Sample Project #4,

Code folder

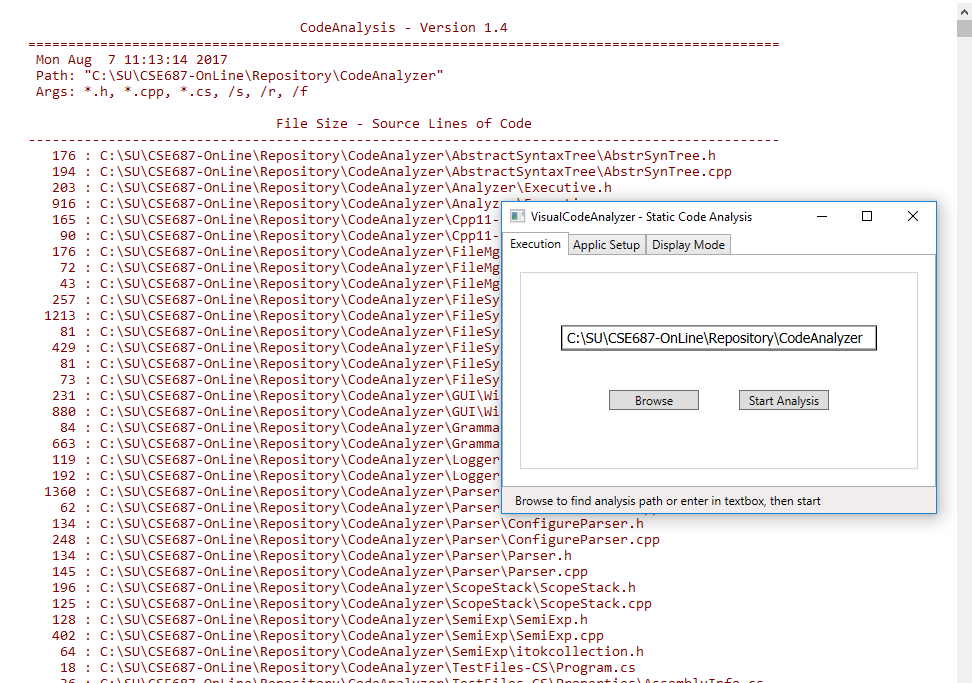

Code Analyzer - analyzes code metrics, SLOCs, and shows AST contents, uses GUI

Software Systems are Structured with Classes and Packages (SMA meets OOD):

The Code analyzer we used for Project #4 Sample is composed of more

than a dozen packages with a total of 10,616 lines of code.

While not "large", it is an industrial scale

project, with some interesting structures, supported by both

application-side and solution-side packages.

We will look at its code, and, package, class, and activity diagrams, to see how an interesting structure can be

implemented with packages:

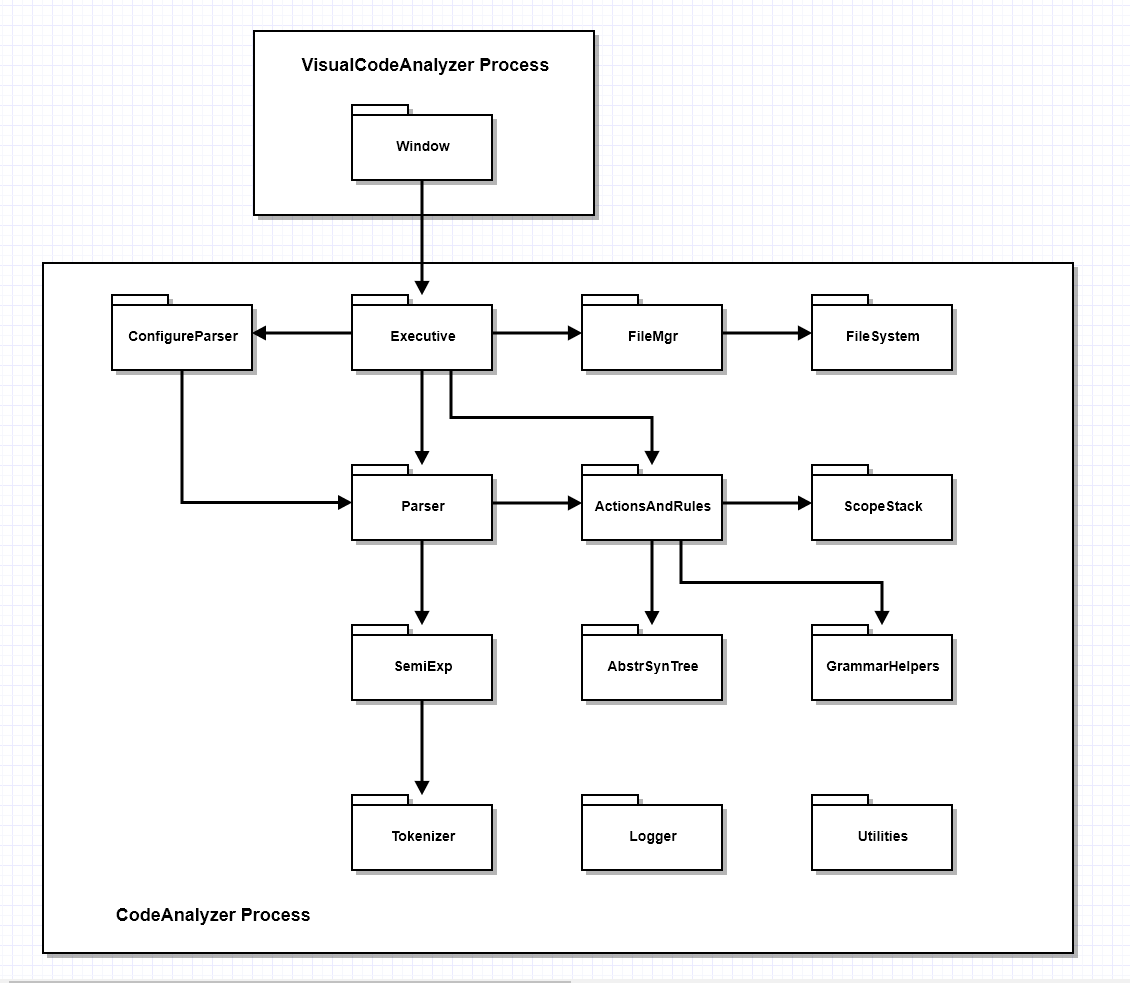

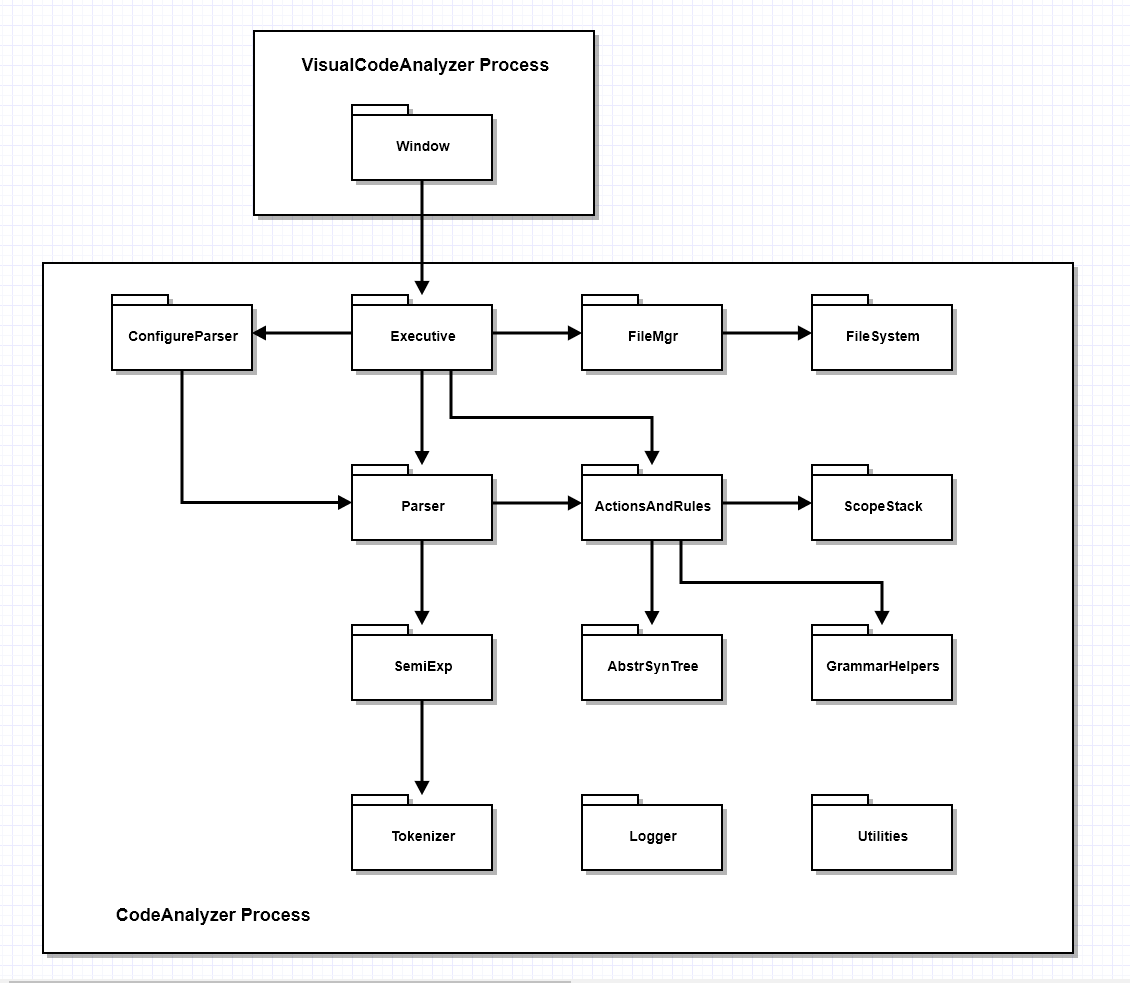

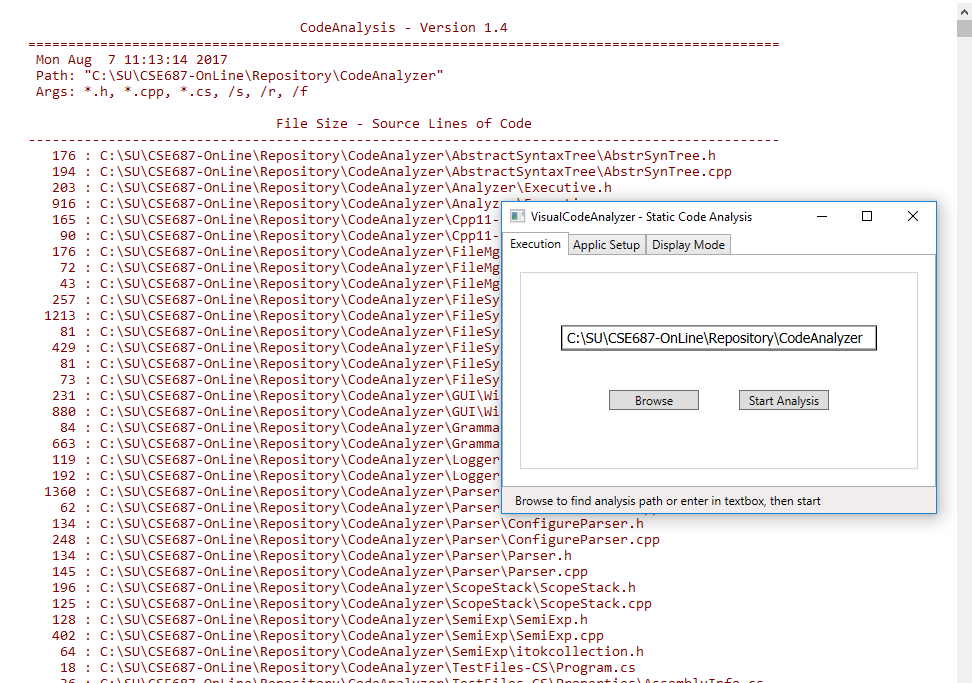

The Visual Code Analyzer application consists of two processes:

This structure turns out to be very effective. We can elect to use the Code Analyzer directly, perhaps in a script.

Most users will use the Visual Code Analyzer GUI. That opens with the last set of attributes selected,

but allows users to selectively change those.

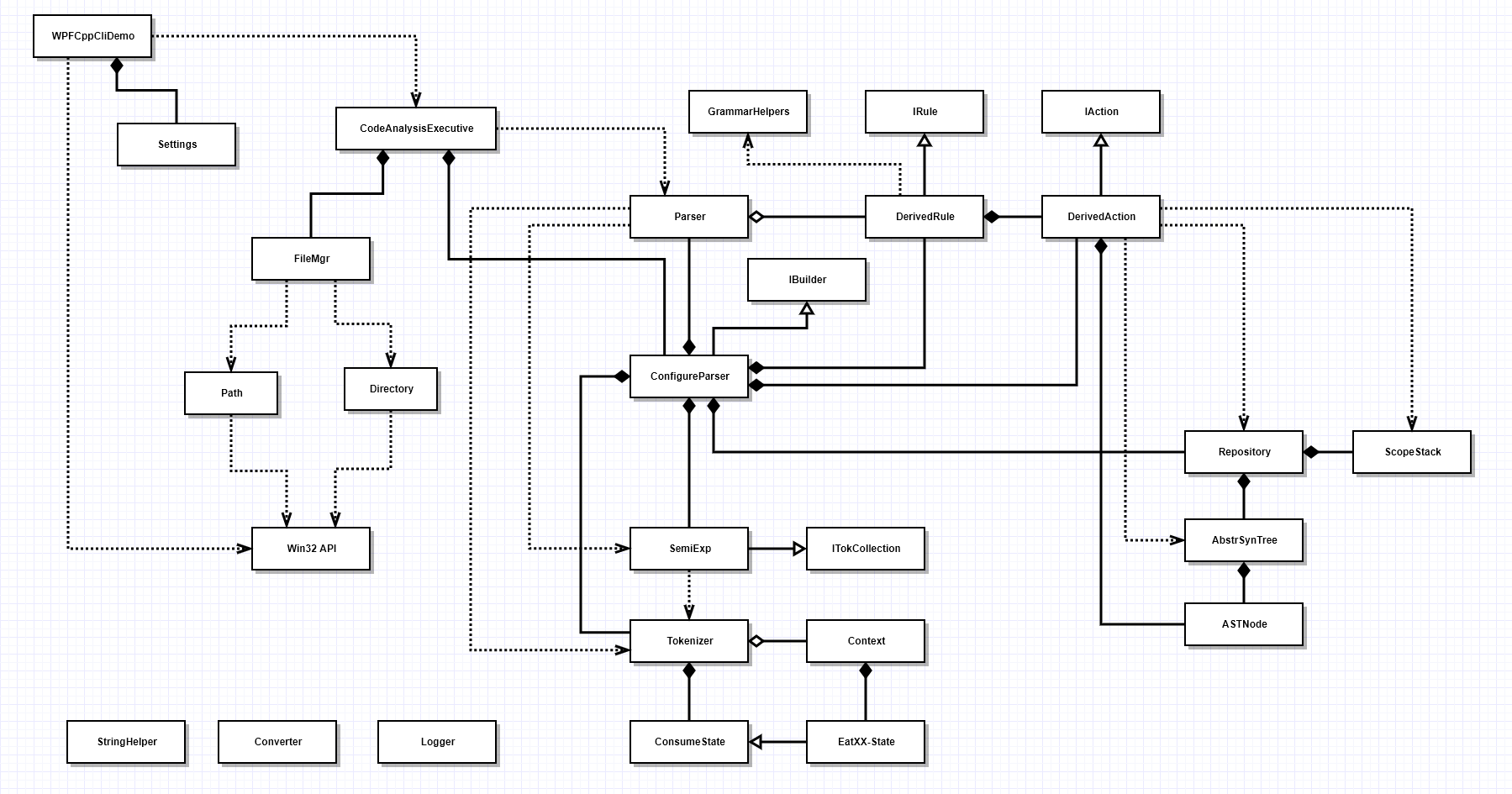

The package diagram is relatively simple, showing us the major parts of the application and how they relate to each other.

This simplicity is a useful abstraction, but it hides a lot of important detail.

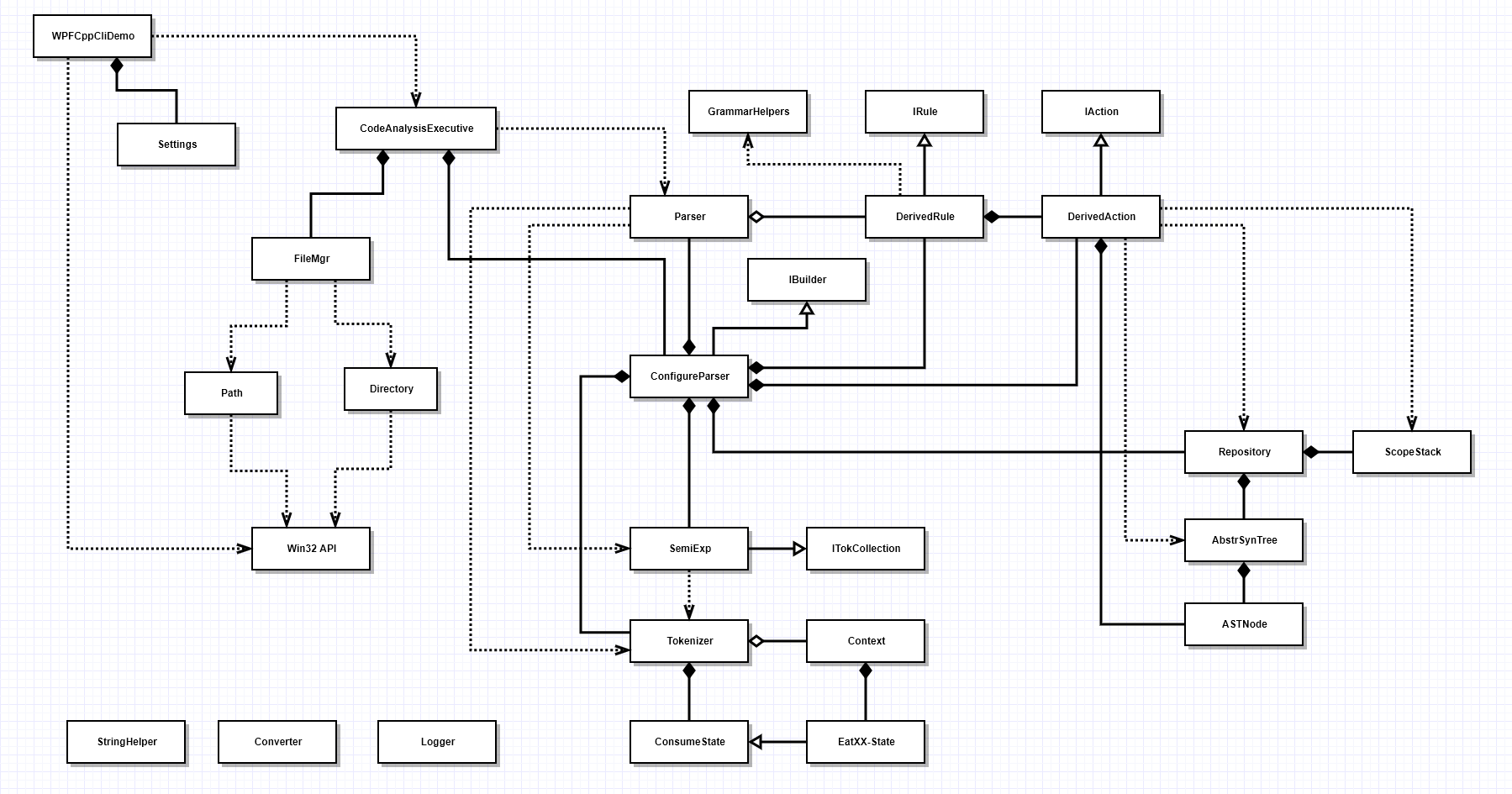

The class diagram makes it clear that there is some significant code complexity in this application. That has to be managed

by dividing the implementation into a number of relatively small and managable classes. When we do that, we have to think carefully

about ownership and communication.

For example, the ConfigureParser instance creates and owns almost all the application's low-level parts, e.g., Parser, Semiexp, Tokenizer,

all the derived Rules, all the derived Actions, and the Repository. Each time it creates a derived action it passes, to the action

constructor, a reference to the Repository. That means that the actions can all access the Abstract Syntax Tree and Scope Stack,

which they need to do to carry out their tasks.

The ownership relationships are clearly show in the class diagram, by means of the composition, aggregation, and using connectors.

Some classes, like GrammarHelpers, are not owned by any other part. This class has all static methods, so no instance is created.

The derived rules simply use it by calling its functions preceded by the class name.

Three classes, StringHelper, Converter - both part of the Utilities package - and Logger are used by most of the classes in the

application. It would be counter-productive to show directly all those associations. That would make the diagram very dense with

association lines and would be almost unreadable. So we simply show them with no associations.

- Code Analyzer accepts the path to code to be analyzed, and a set of analysis attributes, on its command line. It then sweeps through the directory tree rooted at the specified path, and analyzes all the types of files specified in the command line attributes. It has several modes of display, e.g., Code Metrics, Abstract Syntax Tree contents, or Source Lines of Code. The analyser writes a log file at the root of the analysis path, so users can elect to view that later.

- Visual Code Analyzer builds the Code Analyzer's complex command line, supporting browsing for the analysis path and setting the types of analysis display.

,

,

Visual Code Analyzer Packages

Visual Code Analyzer Classes

Visual Code Analyzer Output

In this course, CSE687-OnLine, we've focused on techniques for building individual packages so they are flexible and robust.

We also need the structuring ideas discussed in CSE681-Online,

to help bind all the packages we build into a coherent whole.

Course Review:

A summary of course topics, with links to many of the most important details.

Topics:

Click on titles to expand

-

A large, but elegant, programming language that compiles to native code. It favors enabling users over protecting them.

-

C++ derives most of its language elements and function structure from the C programming language, which in turn, inherited those things from Algol, a European language. It derives its notions of class from SmallTalk.

-

A class is a language construct that binds together member functions and data, providing access to users only to public member functions, not to its data. This encapsulation enables the class to make strong guarantees about validity of its data.

-

For each of your classes, always consciously choose between providing construction, assignment, and destruction operations, allowing the compiler to generate them, or disable them.

-

An abstract data type is simply a value type, e.g., it provides copying, assignment, and move operations that allow instances of the type to behave like built-in types.

-

Templates are compile time constructs that allow us to avoid writing a lot of nearly identical code for classes that could sensibly use any of several concrete types, perhaps as arguments to member functions or as instances of member data. Containers are a good example. Templates are also useful for building functions that accept callable objects, i.e., function pointers, functors, or lambdas. We use template functions to accept instances of any of these distinct types. Thread constructors are a good example. Here are a few interesting examples of template use:

- Defining C++ properties using templates

- Graph class representing networks of nodes connected with arcs

- Demonstration of several ways to traverse m-ary tree structures

-

Classes have four relationships:

-

Inheritance:

A derived class inherits all it's base's members. Non-virtual base functions should not be redefined in the derived class. Virtual member functions may be redefined in the derived class. Pure virtual functions must be redefined. -

Composition:

Instances declared as class data members are composed by the class, creating a strong owning relationship. Composed members are always constructed when the composer is constructed, and destroyed when the composer is destroyed. -

Aggregation:

A class aggregates a data member when it holds a pointer to the member instance on the native heap. Creation of an instance of some type as local data in a member function is also considered to be aggregation. Aggregated instances are owned by the aggregator, but this is a weaker relationship than composition, as the aggregated instances do not exist until code in the aggregator creates them. -

Using:

A class uses an instance of some other class when it is passed the instance to one of its public member funtions by reference. Using is a non-owning relationship and your classes should respect the owning code by doing nothing to invalidate the used instance. Passing an instance by value to a member function is really aggregation, because the receiving class creates and uses its own copy.

-

-

Compound objects are instances of classes that use inheritance, composition, and aggregation of other classes to carry out their mission. We need to be careful, especially with initialization, to ensure they operate as expected. Here is a good example of the initialization and use of compound objects.

-

A functor is a class that defines operator(). That means that instances can be "invoked" like this:

class AFunctor { public: AFunctor(const X& x) : x_(x) {} void operator()(const Y& y) { /* do something useful to x_, using y */ } X value() { return x_; } private: X x_; }; AFunctor func; Y y; func(y); // syntactically looks like a function call func.operator(y); // equivalent to the statement above -

A lambda is an anonymous callable object that can be passed to, and returned from other functions. A lambda is really a short-cut to define a functor. A very useful feature of lambdas is their capture semantics. They can store data defined in their local scope, to be used later when they are invoked.

std::function makeLambda(const std::string& msg) { std::function<void()> fun = [=]() // [=] implies capture by value, [&] implies capture by reference { std::cout << "\n displaying captured data: " << msg; }; return fun; } // in some other scope std::function myFun = makeLambda("hello CSE687-OnLine"); std::cout << "\n using Lambda: " << myFun() << "\n"; -

A callable object is any C++ construct that can be invoked using parentheses, callable(...). Function pointers, functors, and lambdas are all callable objects. Here's a function that accepts and invokes any callable object that takes no arguments:

template<typename T> void invoker(T& callable) // callable could be a lamda with captured data { callable(); // use captured data instead of function arguments } -

Exceptions are a language defined mechanism for handling errors. Exception handling uses instances of std::exception and the key words throw, try, and catch. You should always throw exceptions by value and catch them by reference.

-

A namespace defines a compile-time scope used to distinguish between two or more type or function names with the same value but that have distinct definitions in separate places in code for a single compilation unit. A namespace extends the name of a type, for example, by prepending the type name with the namespace name, i.e., MyNamespace::MyType.

-

The C++ language has a surprisingly short list of dark corners, e.g., compilable constructs that may cause subtle errors. These all have to do with causing Liskov Substitution to fail by improper overloading, overriding, or failing to provide virtual destructors.

-

-

A block of processing instructions, defined by a function passed to the operating system (OS), that executes in a processor core, and is started and stopped by the OS. A thread often runs in an environment containing many other threads that are sequenced in short time-slices by the OS to behave like concurrent processing. A thread may run continuously in a core if there are no other threads contending for that resource. The C++ Standard Library provides the libraries: thread and atomic to support concurrency.

-

An interface for network communication provided by a low-level library. The sockets we discuss are all stream-oriented, reading and writing sequences of bytes. Stream-oriented means that sockets do not provide you with a message structure. If you need that you will have to provide it. In order to communicate these sockets have to be connected. To connect, your code needs, on one end of the channel, a connecter socket and, on the other end, a socket listener, to listen for, and establish a connected channel. You will find that the Sockets library, in our repository, provides good support for building programs using network communication.Sockets Lecture - wk6a, Sockets presentation - pdf

CppSockets code - Socket library

CppStringSocketServer demo code - simple echo server

CommWithFileXfer demo code - sends files, uses Message class -

The standard C++ libraries do not provide any support for Graphical User Interfaces. But it is fairly easy to provide one for a native C++ application by using a C#-based Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) project that communicates with the application through a C++\CLI shim. The WPF-Interop demo is a simple example of how to do this.

-

WPF

A Graphical User Interface (GUI) framework that:- Builds interface windows using a custom XML markup, called XAML, and C# or C++\CLI event handlers.

- Layout model is similar to HTML.

- Provides pervasive dependency relationships between graphical elements and bubbling of events.

- Supports very complete designer control over the appearance and behavior of each window view.

- Runs only on Windows, as a desktop application.

-

C++\CLI

A .Net managed language that runs in a Common Language Runtime (CLR) virtual machine and stores its instances in a managed heap, providing garbage collection, exception handling, and reflection services. C++\CLI code interoperates directly with native C++ code. C++\CLI code and native C++ may be placed in the same file.

Graphical User Interfaces Lecture - wk7a

WPF-Interop demo code - simple example of C# GUI using native C++ code

CSE681-OnLine: Sample Project #4 : Code Repository, written in C# with a useful WPF GUI -

-

The C++ language uses a very well engineered set of standard libraries for I/O, managing data, and using threads, and much more. Each new C++ standard introduces new libraries or new library features. We've focused on these:

-

Streams library

A collection of libraries for stream-based I/O, for the console, files, and in-memory strings. Streams use the insertion operator<<(...) and extraction operator> >(...) to build composable input and output operations. Here is a brief presentation about the structure of the streams library. Almost all of the capabilities of the streams library are demonstrated here: -

STL library - wk9a

The Standard Template Library is a subset of the C++ standard libraries. It provides a large set of containers, each with a defined iterator type, and a set of algorithms designed to operate on the containers. All of the containers are endowed with correct construction, copy, and destruction semantics. Here is a presentation of the structure and top-level properties of the STL. -

Threads library

The Threads library, introduced in the C++11 standardization, contains classes for threads, locks of various kinds, atomics, condition variables, and futures. Futures are interesting because they support returning values computed by child threads, blocking until the result is ready. Here are some useful code demos and resources for programs that use threads:

-

-

These libraries are code that I've written, and hosted on the college server. They supplement the C++ Standard Libraries, providing functionality that does not exist there (as of C++11).

-

FileSystem

A library for managing and queriny Windows directories and their objects. It was written entirely in C++11, using the Win32 API. It has classes File, FileInfo, Directory, and Path, that are modeled after the very well-engineered .Net System.IO library. -

Sockets

A library that provides an abstraction above the Windows sockets library, making many of its operations more user friendly. It provides classes: Socket, SocketConnecter, SocketListener, and SocketSystem. -

C++ Properties

.Net and Java properties provide simple access to class data, without compromising encapsulation. This is a small library designed to provide equivalent functionality. It useful, but also interesting because it illustrates that the C++ language can easily be extended using only features of C++. -

XmlDocument

A library for constructing XML strings and files, and creating a Document Object Model (DOM) instance from well formed XML strings and files.

Custom Libraries - other examples in Repository folder -

-

Links to almost all the presentations and code, ordered by topic.

Course Take-aways:

The most important things we covered in this course are:-

Structure and style for packages:

Packages are the fundamental units of Software Systems. We need to know how to build them well.

Package Structure Matters and Blocking Queue example. -

Syntax and structure of the C++ Language:

C++ is a very effective and expressive language for building packages. We need to know its guiding principles and have an approximate model of the C++ compiler and what it generates in our developer heads.

ADT Lecture, Templates Lecture and Class Relationships Lecture -

Prepackaged Frameworks for building software systems:

There are a rich collection of resources in the C++ ecosystem, and also some surprising omisions. We need to know how to interoperate with code from other languages to use their resources as well.

Standard Library Lecture -

Custom Libraries to support native code operations:

A lot of things that C++ elected not to supply us, we can build, without too much effort, i.e., Sockets, XmlDocument, and CppProperties. Sockets Lecture and our Repository Code. -

Practical project experiences, using all of the above:

Four industrial style projects that progressively build a useful code analysis tool:-

Sample Project #1

Lexical scanner -

Sample Project #2

Rule-based parser -

Sample Project #3

Parser with Abstract Syntax Tree -

Sample Project #4

Code Analyzer

-

Sample Project #1